In August 2024, students flooded the streets of Dhaka. The government opened fire. Hundreds died. The Prime Minister fled to India. Her Home Minister was later sentenced to death for crimes against humanity.

You probably didn’t hear about it.

While Western media obsessed over election polls and culture wars, Bangladesh—a country of 170 million people—overthrew its government in a bloody uprising. Again. Because this is what Bangladesh does. It revolts, violently, then rebuilds under new management, then revolts again a decade or two later.

This isn’t a new story. It’s THE story of Bangladesh for the past 50 years. Military coups. Student massacres. Political assassinations. War crimes tribunals. Rinse and repeat.

And almost nobody in the West pays attention.

Why? Because Bangladesh doesn’t have oil. It’s not strategically vital. It just makes your cheap t-shirts and quietly implodes every couple decades while the world looks away.

But here’s what makes Bangladesh fascinating: it’s not poor because it lacks resources. It has some of the most fertile land on Earth. It’s not unstable because of Western imperialism—though Britain certainly helped set the table. It’s trapped in a cycle of its own making, one that’s simultaneously blessed by geography and cursed by the very abundance that attracted 170 million people to a natural disaster zone in the first place.

Let’s talk about what actually happened to Bangladesh, and why you’ve never heard about it.

The Paradox: Blessed Land, Cursed Geography

Here’s the thing about Bangladesh that nobody tells you: it sits on some of the richest agricultural land on the planet.

The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna river delta—the world’s largest—converges in Bangladesh. Over 57 rivers flow through the country, depositing nutrient-rich alluvial soil across the plains. The annual monsoon floods (yes, the same floods that kill people) act as natural fertilizer, refreshing the topsoil every year.

The result? Rice can be grown and harvested three times per year in many areas. Three harvests. Annually. On the same land.

Compare this to Russia, which has 116 times the land area of Bangladesh but produces only twice as much food. Per square kilometer, Bangladeshi land is roughly 56 times more productive than Russian land.

This fertility is why 170 million people are crammed into an area the size of Iowa. Or, take a look at this comparison with Russia.

For centuries, the land could support massive populations. More food meant more people. More people meant more labor. More labor meant more food. A self-reinforcing cycle that turned the Bengal region into one of the most densely populated places on Earth long before modern population growth.

But here’s the curse: the exact same geography that makes Bangladesh so fertile also makes it a catastrophic disaster zone.

Two-thirds of the country sits less than 15 feet above sea level. It’s a flat river delta. When cyclones roll in from the Bay of Bengal (which funnels storms directly toward Bangladesh’s coast), there’s nowhere for the water to go. Storm surges flood inland. Rivers overflow. Entire regions go underwater.

This isn’t occasional. It’s constant.

Between 1980 and 2008, Bangladesh experienced 219 natural disasters. Cyclones hit almost every year. Major floods in 1987, 1988, 1998, 2007, 2024. The 1970 cyclone killed up to 500,000 people. The 1991 cyclone killed 140,000 and left 10 million homeless.

On average, 700,000 Bangladeshis are displaced every year by natural disasters.

So you have 170 million people living on a flood-prone delta that gets hammered by cyclones annually, packed into one of the most densely populated regions on Earth (1,350 people per square kilometer) because the land was so good at feeding people that nobody left.

The blessing became the trap.

The Cycle: Fifty Years of Revolutions Nobody Noticed

Bangladesh didn’t exist until 1971.

Before that, it was East Pakistan—a bizarre geopolitical arrangement where Pakistan was split into two chunks separated by 1,000 miles of India. West Pakistan (modern Pakistan) controlled the government, the military, and the economy. East Pakistan (Bengal) had the people and produced the exports.

The arrangement was exploitative. West Pakistan diverted foreign aid, controlled trade, refused to share power, and treated East Pakistan as a colony. When East Pakistan’s political party won a democratic election in 1970, West Pakistan refused to hand over power.

So East Pakistan revolted.

The 1971 Liberation War was brutal. Pakistan’s military cracked down. Mass killings. Rape campaigns. Scorched earth. India intervened. Pakistan lost. Bangladesh was born.

The new country’s first leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, tried to implement socialism. It failed spectacularly.

The 1974 famine killed 1.5 million people. Corruption exploded. By 1975, Mujib had declared a one-party socialist state.

He lasted six months.

In August 1975, military officers assassinated Mujib and most of his family in a coup. The new military rulers scrapped socialism, opened the economy, and ruled through the 1980s with a mix of martial law and rigged elections.

Then came the 1990 uprising. Students and workers took to the streets. The military ruler resigned. Democracy was restored.

For a while.

The next three decades were dominated by two political families: the Awami League (Mujib’s party, led by his daughter Sheikh Hasina) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (founded by the 1975 coup leader’s political successors).

They took turns running the country. When one party won, they prosecuted the other party’s leaders. When the other party won, they did the same. Elections were rigged. Opponents were jailed. Violence flared regularly.

Then came 2024.

Student protests erupted over job quotas. The government responded with force. Police and paramilitary units opened fire on unarmed protesters. Students died in the streets of Dhaka.

The violence escalated. On August 5, 2024, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina fled to India as crowds surrounded her residence.

In November 2024, an International Crimes Tribunal sentenced Hasina and her Home Minister, Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal, to death for crimes against humanity during the crackdown.

Kamal had allegedly ordered forces to “use maximum force” against protesters. The tribunal found him responsible for killings in Dhaka and elsewhere.

He’s now in exile, labeled the “Butcher of Bangladesh” by the interim government.

This is the cycle. Students protest. Government kills them. Regime collapses. New government prosecutes the old one. Repeat.

And almost nobody outside South Asia knows it happened.

Corrupto Capitalism: The System That Eats Everything

Bangladesh isn’t just politically unstable. It’s systematically corrupt in a way that goes beyond normal “crony capitalism.”

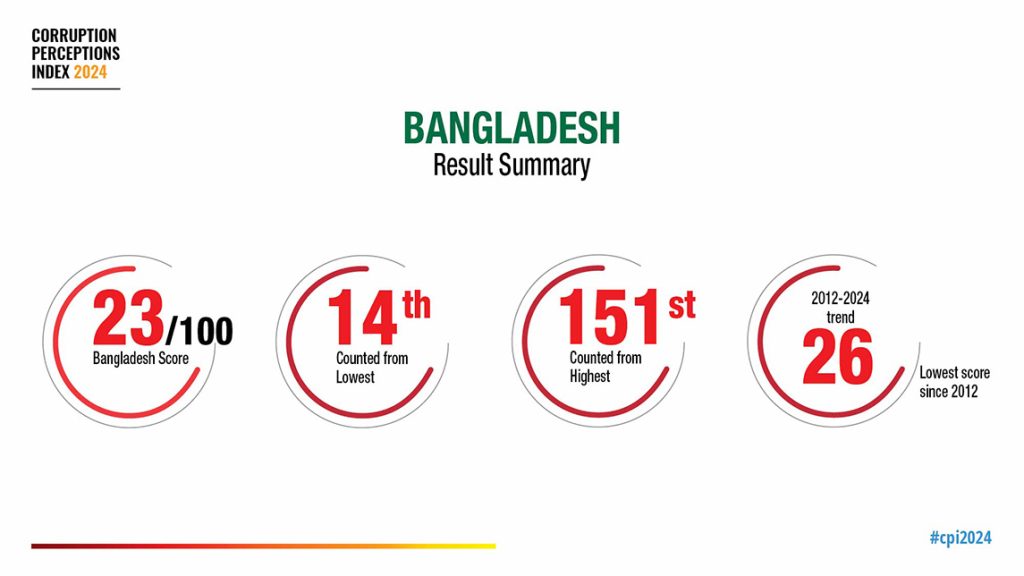

In 2024, Bangladesh scored 23 out of 100 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. That ranks it 151st out of 180 countries—14th from the bottom. Second-worst in South Asia, better only than Afghanistan.

For context, Bangladesh’s corruption score is 10 points lower than the average for Sub-Saharan Africa, the world’s most corrupt region.

This isn’t accidental. Corruption in Bangladesh isn’t a bug in the system. It IS the system.

Here’s how it works:

Every interaction with government requires a bribe. Licensing? Bribe. Customs clearance? Bribe. Building permits? Bribe. Tax assessment? Bribe. Land registration? Bribe. Court case? Bribe.

Prosecutors earn $37.50 per month. They survive on bribes. Police are notoriously corrupt—accepting payments is built into the job. The judiciary is politically controlled. Judges have been caught with fake law degrees.

Even the Anti-Corruption Commission, created in 2004 to fight corruption, is considered “largely ineffective” because the government controls it.

This creates what one Bangladeshi economist calls “corrupting capitalism”—a system where corruption isn’t leakage from the economy, it’s a dominant production input.

In normal capitalism, roughly 60% of revenue goes to labor (wages) and 40% to capital (profits, reinvestment). In Bangladesh, both labor and capital get robbed.

Workers don’t get fair wages because corruption inflates costs at every production step. Businesses can’t reinvest profits because they’re siphoned off through bribes, political tolls, extortion, syndicate fees, and hidden commissions.

The result? Neither workers nor businesses get their share. The middle is eaten by corruption.

And this happens despite Bangladesh having valuable resources:

- Natural gas (7th largest producer in Asia, provides 70%+ of commercial energy)

- Massive garment industry (one of world’s largest exporters)

- Fertile agricultural land (can feed the population 3x over)

- Growing GDP (averaged 6.5% growth from 2004-2020)

The resources exist. The productivity exists. But systematic corruption devours it.

Want an example? The 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse killed over 1,100 garment workers.

The building had been constructed illegally, with massive building code violations. Safety inspections had been paid off. When cracks appeared, workers were ordered back inside anyway.

The factory made clothes for Western brands. The corruption that killed those workers was homegrown.

The Colonial Legacy (But Not an Excuse)

People often blame Bangladesh’s problems on Western imperialism. There’s some truth to that. But it’s complicated.

British colonial rule in Bengal (1757-1947) was devastating:

- The 1770 Bengal Famine killed 10 million people, largely due to British tax policies during drought

- Britain extracted an estimated $45 trillion from the Indian subcontinent over two centuries

- The British dismantled Bengal’s textile and cottage industries to protect British manufacturing

- They introduced exploitative tax systems and built a bureaucracy designed for extraction, not governance

- Capital from Bengal literally funded Britain’s Industrial Revolution

The legacy is real. Bangladesh inherited a corrupt bureaucratic system designed to extract wealth, not serve the public.

But here’s the thing: Britain left in 1947. That was 78 years ago. Bangladesh has been independent since 1971—54 years.

At some point, you own your own system.

The corruption in Bangladesh today isn’t British officials demanding bribes. It’s Bangladeshi officials. The political violence isn’t colonial soldiers shooting protesters. It’s Bangladeshi security forces. The rigged courts and fake judges aren’t holdovers from the Raj. They’re products of decades of Bangladeshi governance.

Yes, the British built the foundation. But Bangladesh’s elite found the corrupt bureaucracy too profitable to dismantle. They inherited a broken system and chose to get rich from it rather than fix it.

There’s a deeper irony: Bangladesh’s stolen money doesn’t stay in Bangladesh. It flows to Western financial centers.

According to Transparency International, the countries receiving the most money laundered from Bangladesh include: Singapore (3rd on corruption index), Switzerland (5th), Australia (10th), Canada (15th), UK (20th), UAE (23rd), and US (28th).

The “clean” countries profit from Bangladesh’s corruption. They lecture Bangladesh about governance while their banks accept billions in laundered assets.

So the West’s role isn’t simple imperialism anymore. It’s more subtle: Britain created the system, Bangladesh’s elite maintained it, and Western financial centers profit from it.

Everyone wins except the Bangladeshi people.

Why the West Doesn’t Care

Let’s be honest about why Bangladesh’s revolutions are invisible.

It’s not a conspiracy. It’s just incentives.

No Strategic Value: Bangladesh doesn’t have oil. It’s not on a critical trade route. It doesn’t threaten regional stability in ways that affect Western interests. Yes, it has natural gas, but not enough to matter globally.

What does Bangladesh produce? Garments. Your cheap H&M t-shirts. Your fast fashion. Important for consumers, irrelevant for geopolitics.

No Media Hook: Western media covers international stories when they have a clear narrative that resonates with Western audiences. Ukraine? Russian aggression threatens Europe. Israel-Palestine? Historical ties, religious significance, US involvement.

Bangladesh student uprising? There’s no clear “good guys vs bad guys” frame that works for Western audiences. It’s complicated internal politics in a country most Americans couldn’t find on a map.

The Coverage Gap: When Sheikh Hasina fled and her government collapsed in August 2024, it barely made Western headlines. When she was sentenced to death in November, even less coverage.

Compare this to Ukraine, which gets 24/7 coverage. Or even smaller conflicts that touch Western interests.

Bangladesh can have a revolution, sentence its former PM to death, and Western audiences will never know it happened.

Institutional Indifference: Here’s the deeper structural issue: the same institutional investors who own Western companies also own stakes in companies across South Asia.

BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, Fidelity—these firms manage trillions and own pieces of everything. When you own both Company A and its competitor Company B across multiple countries, you don’t really care about individual country instability. You care about portfolio returns.

Bangladesh’s corruption? Doesn’t move the needle. Student protests? Irrelevant unless they disrupt garment exports. Political violence? Only matters if it threatens quarterly earnings.

The system isn’t designed to care about 170 million people trapped in a cycle of violence and corruption. It’s designed to extract value—garments, in this case—while minimizing volatility in the portfolio.

The Bitter Truth: Your clothes are cheap because Bangladeshi workers are exploited. The system is corrupt because it’s profitable. The violence continues because nobody with power has incentive to stop it.

And when the next revolution comes—because it will—you probably won’t hear about that one either.

The Pattern That Won’t Break

So here’s where Bangladesh stands in 2026:

- 170 million people crammed into a disaster-prone river delta

- Some of the world’s most fertile land, regularly destroyed by floods and cyclones

- A 50-year cycle of revolutions, coups, and violence

- Systematic corruption (23/100 score) that devours productivity

- A former Prime Minister and her Home Minister sentenced to death, in exile

- Western indifference interrupted only by cheap garment orders

- An interim government trying to reform a system that’s been profitable for decades

The pattern is clear. Students will protest again. The government will crack down. Violence will erupt. The regime will fall or survive. Either way, corruption will continue because it’s baked into every transaction.

The land will keep feeding people and killing them with floods. Western banks will keep accepting laundered money. Media will keep ignoring the violence. And the cycle will repeat.

Because nobody with the power to break the pattern has any incentive to do so.

Bangladesh isn’t a tragedy. It’s a system working exactly as designed.

Just not for the people who live there.

Oh, and in case you missed it: there was a revolution in Bangladesh in 2024. The Prime Minister fled.

Her Home Minister was sentenced to death for shooting students. The country is being run by an interim government led by a Nobel Peace Prize winner.

You probably didn’t hear about it.

Because Bangladesh’s revolutions are invisible.

Until the next one.

No responses yet