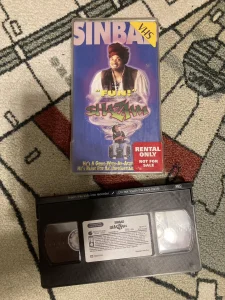

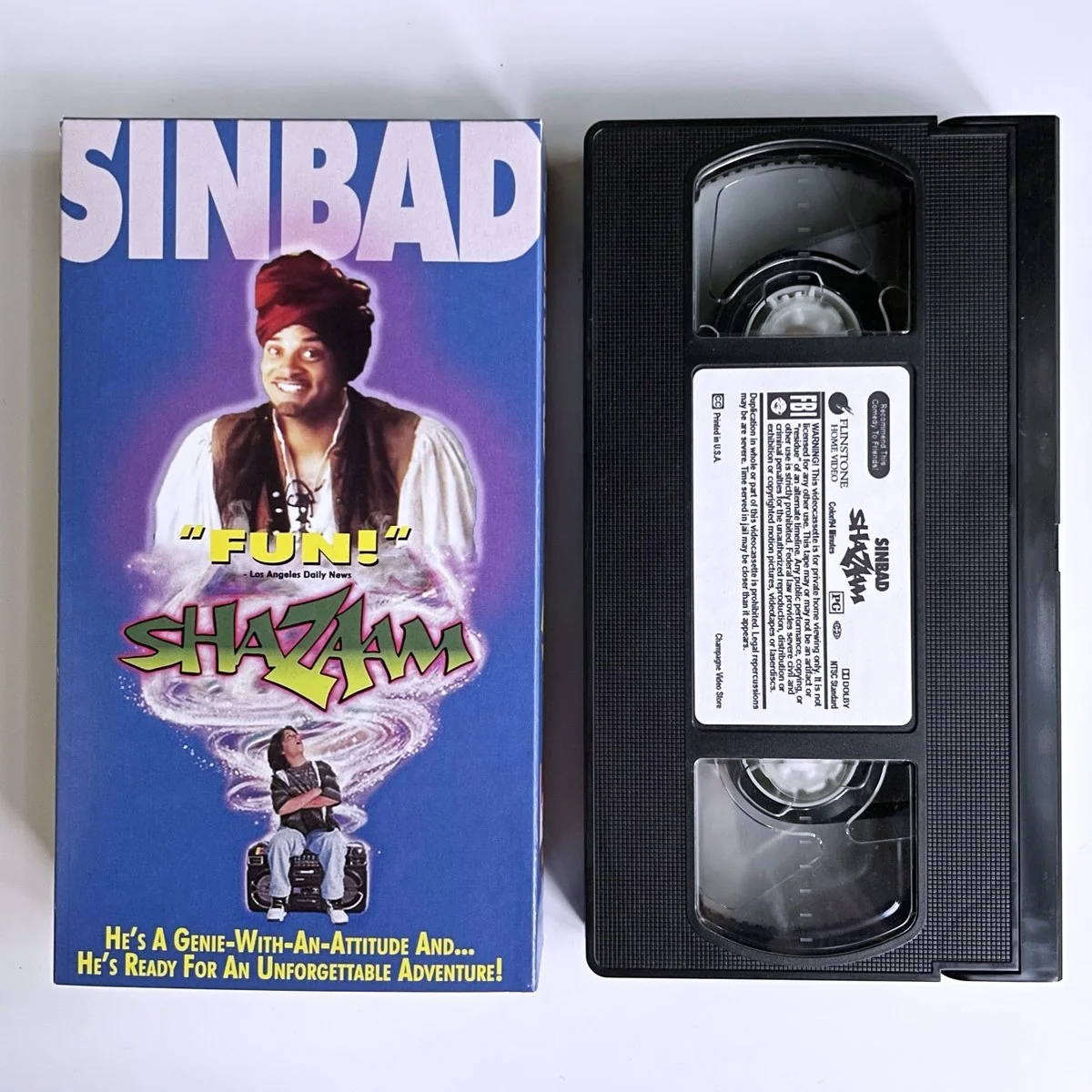

Thousands of people insist they watched a 1990s movie called “Shazaam” starring comedian Sinbad as a genie. They remember specific plot details, the VHS box art, renting it from Blockbuster, even watching it multiple times as children. Some claim it was their favorite movie. Others say it introduced them to Sinbad as an actor. There are even videos on Youtube of people grabbing the movie from their collection and showing it to the camera.

There’s just one problem: the movie never existed.

Not “it’s hard to find.” Not “it’s lost media.” It never existed. There is no record of its production, no cast, no crew, no copyright filing, no VHS release, no reviews, and no physical copies despite thousands claiming to own it.

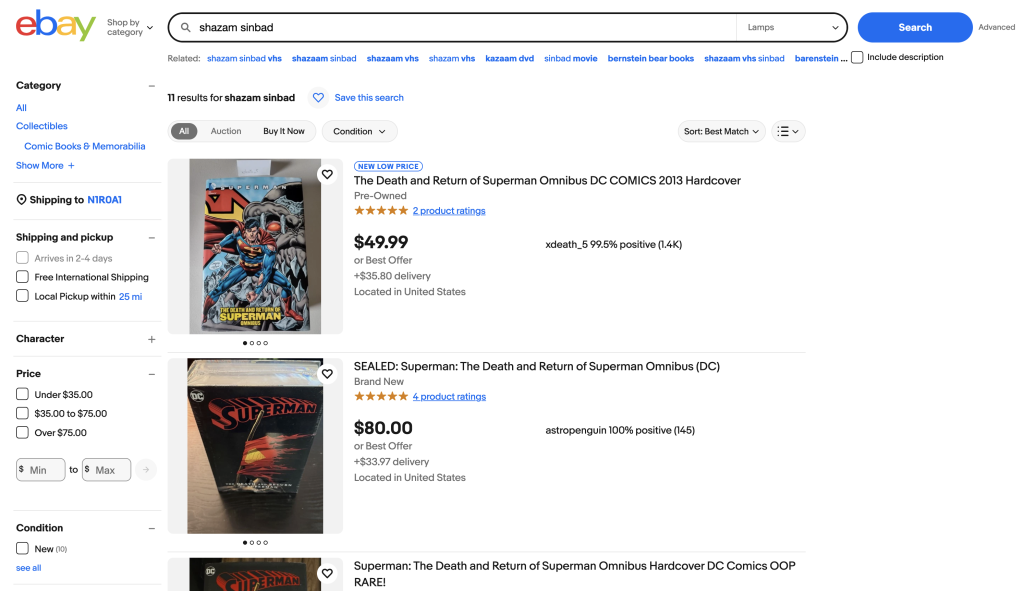

Try this – go on ebay right now and see if anyone has it for sale. Well?

So everyone who had this movie in storage…it’s just gone? No one wants to sell the real deal and make 10K? Little gremlins came into everyone’s house, and stole it from their movie shelves?

Lookie here, this isn’t a fringe conspiracy theory. It’s one of the most well-known examples of the “Mandela Effect”—a term for when large groups of people share the same false memory. But unlike more ambiguous cases (did the Monopoly Man have a monocle?), Shazaam is particularly fascinating because the false memory is so specific, so detailed, and so fiercely defended.

So what actually happened? Let’s examine the evidence—or rather, the complete absence of it—and the psychology behind how an entire generation convinced itself it watched a movie that was never made.

The Claims: What People “Remember”

Before we debunk…or shall we say “deboonk” this (as the kids say), let’s be clear about what people claim:

- The movie was called “Shazaam” (sometimes spelled “Shazam”)

- Sinbad played a genie in a purple and gold (or blue, depending on who you ask) costume

- It came out in 1993 or 1994 (or 1996, accounts vary)

- It involved two kids who find a magic lamp

- It was widely available on VHS at Blockbuster and other rental stores

- Teen heartthrob Jonathan Brandis was one of the child actors

- McDonald’s had promotional toys for the movie

- It aired on Disney Channel in July 1994

- There was a poster in Disney Channel Magazine from June/July 1994

People don’t just vaguely remember “Sinbad dressed like a genie.” They have elaborate plot descriptions: kids in an attic finding their grandmother’s belongings, a scene at a county fair, Sinbad granting wishes that go wrong, railroad tracks, a romantic subplot. One person on Reddit wrote a 1,000+ word synopsis with character names, scene descriptions, and dialogue.

The confidence is absolute. When challenged, responses include:

- “I watched it hundreds of times”

- “I owned it on VHS”

- “It was my favorite childhood movie”

- “I worked at a video store and saw the box every day”

- “I would bet my life on it”

So with this many people, with this much detail, with this much conviction—surely there must be something to it, right?

Wrong.

The Evidence: 30 Reasons Shazaam Never Existed

Hard Evidence Problems (The Smoking Guns)

1. No IMDb Entry Every film ever theatrically or direct-to-video released has an IMDb page with production details, cast, and crew. Shazaam has none. You can’t scrub a movie from IMDb—it’s a permanent database.

2. No Copyright Registration The U.S. Copyright Office maintains records of every copyrighted film. No registration for “Shazaam” starring Sinbad exists. This is public record and easily searchable.

3. No ISBN/UPC for VHS Release Every VHS tape had a barcode and catalog number. Video stores used these for inventory management. No such number exists for Shazaam. Video store database archives exist—Shazaam isn’t in them.

4. No One Can Quote Dialogue Despite claims of watching it “hundreds of times,” when challenged to quote even ONE line of dialogue, people either refuse, make excuses, or go silent. This is devastating. Everyone can quote lines from movies they saw once 30 years ago. But from their “favorite childhood film”? Nothing.

5. No Co-Stars Can Be Named Challenge: Name the child actors. Name ANY other actor besides Sinbad. People claim Jonathan Brandis was in it, but his complete filmography is documented—no Shazaam. No other actor has ever been definitively named.

6. No Physical Copies Exist If this had a wide VHS release as claimed, there would be thousands of copies in circulation. ebay, Mercari, garage sales, estate sales—nothing. Compare this to actually obscure ’90s movies like “Mac and Me” or “The Peanut Butter Solution”—physical copies of those exist and surface regularly.

7. No Production Company Records Movies leave massive paper trails: contracts, location permits, insurance policies, guild registrations. Shazaam has zero documentation in SAG (Screen Actors Guild), DGA (Directors Guild), or WGA (Writers Guild) records.

8. No Film Critics Reviewed It Not one review exists in any newspaper, magazine, Siskel & Ebert, or trade publication. Even terrible direct-to-video movies get reviewed somewhere. One person would at least swear to Jesus that they saw or read Leonard Maltin’s opinion on the matter, instead there’s this: Shazam! review

9. No McDonald’s Promotional Toys Someone claimed McDonald’s had Happy Meal toys—a spinning lamp with Sinbad inside. McDonald’s keeps comprehensive archives of every promotional campaign. No Shazaam toys exist in any collector database, and Happy Meal toy collecting is an obsessive hobby with meticulous documentation.

10. No Cast or Crew Remember It Hundreds of people work on films—actors, directors, cinematographers, grips, PAs, craft services, stunt coordinators. Not ONE person involved in making a feature film has come forward. No “I was an extra” stories, no crew member anecdotes, nothing.

11. Sinbad Himself Denies It The man himself has repeatedly said it never happened. Yes, he made joke videos sarcastically “admitting” it (saying he needed “crack money” and the CIA destroyed all copies), but these are obviously satirical.

12. No Production Photos Movies generate thousands of behind-the-scenes photos: on-set pictures, promotional shots, candid crew photos. Zero exist for Shazaam.

13. No Film Permits Cities require permits for filming. These are public records. No permits exist for a Sinbad genie movie.

14. No Box Office Data If it had even a limited theatrical release, there would be box office tracking. Nothing exists in any database.

15. No Video Store Employees Confirm It Despite thousands of people claiming they “worked at Blockbuster and saw it every day,” not one video store employee has produced rental records, inventory lists, or returns documentation.

The “I Have Proof” Problem

16. “I Have the VHS But Can’t Find It” Multiple people claim: “It’s in storage,” “I have to go through 1,000 VHS tapes,” “I recorded it off TV and didn’t label it.” Years later: still searching. This is an unfalsifiable claim—convenient, isn’t it?

17. “I Have Photos of the VHS Box Somewhere” People claim to have photos. Okay, post them. You have a smartphone. Takes 10 seconds. Nobody ever does. When images do surface, they’re fan-made recreations or photoshopped mockups.

18. The ThinkGeek “Sale” Was an April Fools’ Joke Someone claimed you could buy it on ThinkGeek.com. This was an April Fools’ Day prank. People cited it as “proof.”

19. No One Can Describe the Ending When asked “How does the movie end?”, responses are either silence, vague hand-waving, or contradictory descriptions. Real movies have endings people remember.

20. No Trailer Exists People claim they saw commercials/trailers constantly. Where are they? TV commercial databases exist. Trailer archives exist. Nothing.

The Contradiction Problem

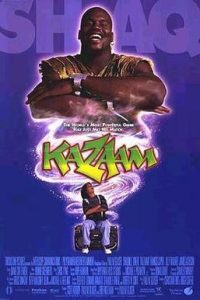

21. The Release Date Changes Some say 1993, others 1994, still others 1996. This matters because the “Kazaam was a ripoff” narrative only works if Shazaam came first—but even believers can’t agree when it supposedly came out.

22. The Costume Description Changes Purple and gold? Blue? Red? No shirt under the vest? Full costume? The details contradict each other. Real movies don’t have this problem—everyone agrees on what characters wore.

23. Plot Details Contradict One kid or two? Their names? What happens? People’s “memories” don’t align on basic plot points.

24. The Jonathan Brandis Problem Multiple people name him as the kid actor. His complete filmography is public and well-documented (he was a teen heartthrob—fans tracked everything). No Shazaam. If a recognizable actor was in this “widely released” film, it would be in their credits.

25. The Disney Channel Magazine Poster Someone claims there was a poster in the June/July 1994 issue. Disney Channel Magazine archives exist. Collectors have every issue. No such poster exists.

The Trolling Problem

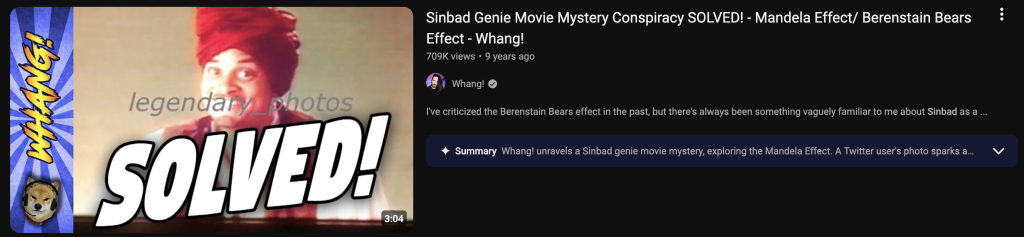

26. People Are Having Fun Lying YouTubers make money from “Mandela Effect PROOF!” videos. People sell “replica” VHS covers on Etsy. Facebook trolls write elaborate fake plot synopses. It drives engagement. Some people just enjoy the chaos.

27. The 2017 CollegeHumor Parody CollegeHumor made a comedy video where they got Sinbad (in his 60s) to dress as a genie and film a “recreation” mocking the Mandela Effect. It includes Easter eggs: Berenstein Bears (it’s Berenstain), Monopoly Man with a monocle (he never had one), Curious George with a tail (he doesn’t have one). This is SATIRE. People now cite this parody as “proof” the movie existed, claiming “that’s exactly how I remember it.” Look at Sinbad’s neck—it’s 2017 Sinbad, not 1994 Sinbad.

28. The “Crack Money” Video Is a Joke Sinbad made a satirical video about “needing crack money” and the CIA destroying all copies. This is him mocking the conspiracy. People cite it as him “admitting it.”

The Pattern Problem

29. Memory Cross-Contamination Once someone reads “Jonathan Brandis was in it” or “it aired on Disney Channel July 1994,” other people’s brains incorporate those details. Now THEY “remember” those things too, even though they never thought about them before reading it.

30. No One Uploads It This is the most damning evidence: If even ONE person who claims to own it would upload 30 seconds of footage to YouTube, this debate would be over. The fact that nobody has done this in over a decade—despite thousands claiming to own it—tells you everything.

What Actually Happened: The Psychology

So if the movie never existed, where did this incredibly specific, widely shared false memory come from? The answer lies in understanding several psychological phenomena working together.

Source #1: Kazaam (1996)

The actual genie movie that existed was Kazaam, starring Shaquille O’Neal as a genie. It came out in 1996, was widely panned, and is exactly the kind of mediocre ’90s kids movie people vaguely remember.

The confusion:

- Shaquille O’Neal and Sinbad were both popular Black entertainers doing family-friendly content in the mid-’90s

- Both were known for their larger-than-life personalities

- Both were in the “guy who’s famous for something else tries acting” category

- The names are similar in rhythm: “Sinbad” and “Shazam/Kazaam”

- Both wore flamboyant outfits

For someone who saw Kazaam once as a kid in the ’90s, the brain filing it under “that genie movie with the funny Black guy” is completely normal. The confusion between Shaq and Sinbad isn’t racist—it’s how memory works when you weren’t paying close attention as a child.

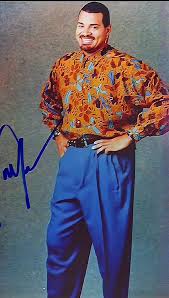

Source #2: Sinbad’s Aesthetic and Persona

Sinbad in the ’90s:

- Wore baggy MC Hammer-style pants constantly

- Favored vests and flamboyant colors

- His stage name is literally “Sinbad”—as in “Sinbad the Sailor,” a character deeply associated with Arabian Nights, genies, and magic

- His entire comedic persona was high-energy, physical, family-friendly

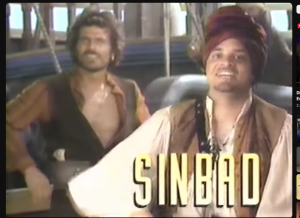

The 1994 TNT Marathon: In 1994, Sinbad hosted a TNT movie marathon of old “Sinbad the Sailor” films. He dressed in a pirate costume with a turban—which to a kid looks like a genie outfit. This is the SOURCE IMAGE people remember. He introduced old adventure films while dressed in Middle Eastern-inspired clothing.

People saw this, filed it away as “Sinbad dressed as a genie,” and their brains did the rest.

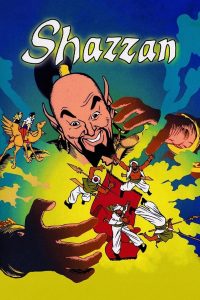

Source #3: The Shazzan Cartoon (1967)

Hanna-Barbera produced a cartoon called “Shazzan” (note: two z’s) about a genie. It aired in the late ’60s but had reruns on cable throughout the ’80s and ’90s.

The title similarity to “Shazaam” is striking. Kids who saw both Shazzan reruns and Sinbad in the ’90s could easily conflate them.

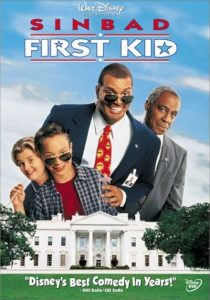

Source #4: Other ’90s Sinbad Movies

Sinbad appeared in several family movies in the mid-’90s:

- First Kid (1996) – same year as Kazaam, often rented alongside it

- Jingle All the Way (1996) – playing an annoying, over-the-top character

- Houseguest (1995)

These movies existed, were watched, and featured Sinbad’s energetic comedic style. Memories of these blend together with Kazaam.

Source #5: The Psychology of False Memory

Now we get to the cognitive mechanisms that transformed vague confusion into concrete false memories:

Confabulation: When your brain has a gap in memory, it fills it in with plausible details. You remember “a genie movie from the ’90s with a comedian” and your brain fabricates details to make the memory coherent: a plot, a VHS cover, the act of renting it.

False Recognition: When someone describes the movie (or you see the CollegeHumor parody), your brain experiences a feeling of familiarity. “Yes! That’s what I remember!” But you’re not remembering the original—you’re recognizing the suggestion as plausible, and your brain treats recognition as memory.

Source Confusion: Your brain stores “Sinbad in flamboyant outfit,” “genie movie,” “1994 TNT,” “Kazaam,” and “First Kid” separately. When you try to recall “that genie movie,” your brain combines elements from multiple sources into one composite “memory.”

Social Proof: Once you see other people saying “I remember it too!”, your brain treats this as validation. “I’m not crazy—other people remember it!” This strengthens the false memory, making it feel more real.

Confirmation Bias: Once you believe you remember it, you seek evidence that confirms your belief and dismiss contradictory evidence. “Sinbad denies it? Of course—he’s embarrassed.” “No physical copies exist? The government must have destroyed them.”

Cognitive Dissonance: Admitting you’re wrong creates psychological discomfort. It’s easier to believe in alternate timelines or conspiracy theories than to accept that your memory is faulty. This is ego protection.

Source #6: The Internet Echo Chamber

Here’s where it gets really interesting: the internet didn’t just spread the false memory—it elaborated and calcified it.

The mechanism:

- Someone posts online: “Does anyone else remember a Sinbad genie movie called Shazaam?”

- A few people respond: “Yes! I remember that!”

- Someone adds details: “It had two kids, they found a lamp…”

- Someone else adds: “I think Jonathan Brandis was in it…”

- Another person: “It aired on Disney Channel in 1994…”

- Another: “There were McDonald’s toys…”

Now everyone reading this thread absorbs all these details. When they try to recall their vague memory of “something with Sinbad and a genie,” their brain fills in the gaps with these suggested details. They now “remember” Jonathan Brandis, Disney Channel, the McDonald’s toys—even though they never thought about these things before reading about them.

The confabulation cascade: Person A contributes one false detail. Person B reads it and adds another. Person C reads both and adds a third. Each new detail makes the collective “memory” more elaborate and specific. Now everyone has a detailed, consistent story—but it’s a story they co-created, not remembered.

The 2017 CollegeHumor video accelerated this: When CollegeHumor released their parody with Sinbad in a genie costume, people watched it and thought: “That’s EXACTLY what I remember!” But they’re not remembering the original—they’re experiencing false recognition of a parody made 20+ years later. Look at the screenshot: Sinbad has an old man’s neck. This is 2017 Sinbad, not 1994 Sinbad. But the emotional feeling of recognition is so strong that people cite this obvious parody as “proof.”

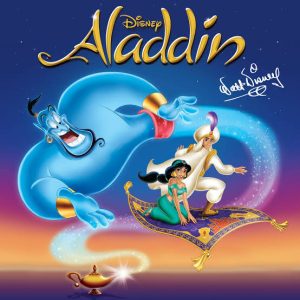

Source #7: The Aladdin Effect

Disney’s Aladdin (1992) was a massive cultural phenomenon. Robin Williams as the Genie was iconic. The movie created a wave of genie-themed content in the mid-’90s.

The false context: People’s brains create a plausible backstory: “Of course there were multiple genie movies in the ’90s—everyone was trying to capitalize on Aladdin’s success. Sinbad doing a live-action genie movie makes perfect sense.”

This invented context makes the false memory feel MORE plausible, which strengthens it further.

One person on GameFAQs wrote: “When Sinbad came out as the Genie it was like a homage to Robin Williams as Aladdin.”

This sounds reasonable. It feels true. But it’s confabulation—inventing a motivation for something that never happened.

The “I’m Right Because I Remember” Trap

Here’s the most fascinating psychological aspect: people believe their memory is evidence.

On Reddit, someone wrote: “We have our memories. They’re real. No one can take that from us.”

This statement reveals the epistemological trap: the person has made their subjective memory unfalsifiable. No amount of evidence can disprove it because they’ve decided their internal experience is more reliable than external reality.

This is the same reasoning that allows for:

- Conspiracy theories (no evidence = cover-up)

- Pseudoscience (lack of proof = suppression by Big Pharma)

- False accusations (I remember it happening = it happened)

When challenged, believers respond with:

- “You’re just too young to remember”

- “We crossed into a different dimension”

- “The government erased all evidence”

- “Sinbad is lying because he’s embarrassed”

Notice the pattern: every piece of contradictory evidence is reframed as supporting evidence. This is unfalsifiability in action. If you had it in the basement in a box, go down there right now and get it and show it on the internet. Or, are you saying that someone stole it? Or someone beamed it out of that box at some point? Is that it??!

The Real Test: Specificity vs. Vagueness

Here’s how you can tell this is a false memory rather than suppressed truth:

If Shazaam was real, people would be able to:

- Quote dialogue (they can’t)

- Name co-stars definitively (they can’t)

- Agree on plot details (they don’t)

- Describe the ending coherently (they can’t)

- Produce a physical copy (they haven’t)

- Point to ANY documentary evidence (there is none)

Instead, what people can do is:

- Describe vague feelings (“I remember the VHS box being white”)

- Provide contradictory details (purple costume vs. blue costume)

- “Recognize” the CollegeHumor parody as authentic

- Insist their memory is real despite zero evidence

This is the signature of false memory: strong emotional conviction, vague details, inability to be specific when challenged.

Why This Matters

The Shazaam phenomenon isn’t just a quirky internet mystery—it reveals something profound about how memory works, how social validation shapes belief, and how the internet can manufacture consensus reality.

What we learn:

1. Memory is unreliable Even vivid, confident memories can be completely false. The strength of your conviction is NOT evidence of accuracy.

2. Social proof is powerful When other people validate your false memory, it becomes stronger. Communities can collectively believe things that never happened.

3. The internet amplifies false memories Online spaces allow people to share, elaborate, and validate false memories at scale. What might have been a private “wait, didn’t Sinbad…?” becomes a detailed, shared “reality.”

4. Cognitive dissonance is hard to overcome Once you’ve publicly committed to a belief, admitting you’re wrong is psychologically painful. It’s easier to invent elaborate explanations (alternate timelines, government cover-ups) than to simply say “I was mistaken.”

5. Unfalsifiable beliefs are dangerous When people decide their memory is more real than documentary evidence, we enter dangerous territory. This is the same mechanism behind false accusations, conspiracy theories, and the breakdown of shared reality.

The Verdict

Shazaam never existed. Not in this timeline, not in any timeline. There was no Sinbad genie movie.

What existed was:

- Kazaam (1996) with Shaq

- Sinbad hosting a 1994 TNT pirate movie marathon in Middle Eastern costume

- Sinbad’s general aesthetic and persona

- The Shazzan cartoon from 1967

- Multiple ’90s Sinbad movies (First Kid, Jingle All the Way, Houseguest)

- Normal human memory confusion

- Social media validation and elaboration

- A 2017 CollegeHumor parody

These elements combined in people’s minds, reinforced by internet communities, and calcified into a detailed false memory that thousands now defend with absolute certainty.

You didn’t watch Shazaam as a kid. You watched Kazaam, or you saw Sinbad in something else, or you saw him dressed as Sinbad the Sailor, and your brain filed it all under “that genie thing.”

That’s not an alternate timeline. That’s just how memory works.

The good news: being wrong about a ’90s movie doesn’t make you stupid. It makes you human. Memory is fallible. That’s normal.

The bad news: if you’re still insisting it existed after reading this, you might want to examine why admitting you’re wrong is so psychologically difficult. Because that—not the movie—is the real mystery worth exploring.

Challenge for believers: Upload 30 seconds of footage. Just 30 seconds. That’s all it would take to prove everyone wrong. Don’t put the video in and then stop recording. Be in the video, sit down, watch the movie. Break the internet.

The closest thing that Sinbad himself said that sounds the most plausible is he made it for crack money, but the rest of it – timelines switching, Sinbad and black ops robbing your parents closet (where the video USED TO BE I SWEAR), the shadow government and masons having a laugh at your expense – that’s all bunk until someone brings the goods and proves it to the world conclusively.

Until then, the evidence is overwhelmingly clear: your memory betrayed you, the internet validated the betrayal, and your ego won’t let you admit it.

And that’s the real Mandela Effect.

No responses yet